On February 6th in a beautiful meeting room at the College Club in Boston, the Garden Club of the Back Bay hosted a presentation by Betsy Grecoe who took us on an exploration of colonial gardening. Photos of her trips to Colonial Williamsburg, Mount Vernon, Monticello, the John Quincy Adams house, and the Whipple House in Ipswich illustrated the garden style of the 17th to early 19th centuries.

On February 6th in a beautiful meeting room at the College Club in Boston, the Garden Club of the Back Bay hosted a presentation by Betsy Grecoe who took us on an exploration of colonial gardening. Photos of her trips to Colonial Williamsburg, Mount Vernon, Monticello, the John Quincy Adams house, and the Whipple House in Ipswich illustrated the garden style of the 17th to early 19th centuries.

Betsy, who is a retired high school English teacher and was vice president of the Tewksbury Garden Club, has traveled with her husband up and down the east coast to visit these gardens as well as others.

The Beginning

Colonial gardens, at least in the beginning, were mainly for sustenance gardening – growing vegetable and herbs for the family. Raised beds were built with boards or rocks to hold the soil. These gardens grew vegetables we are familiar with today such as carrots, cabbage, turnips, and onions.

Colonial gardens, at least in the beginning, were mainly for sustenance gardening – growing vegetable and herbs for the family. Raised beds were built with boards or rocks to hold the soil. These gardens grew vegetables we are familiar with today such as carrots, cabbage, turnips, and onions.

Most of the gardens, however, were “physic” gardens – herbs grown for medicinal purposes – and included lavender (also used as an insecticide), valerian, lemon balm, ladies bed straw (yellow flowered plant used for sore muscles), comfrey, tansy, rose hips, rosemary (used to improve memory). However, herbs, such as St. John’s wort, were also used as dyes for fabric and yarn as were black walnut hulls. And, of course, they were also used for cooking such as chives, sage, basil, and lovage (tastes like celery).

Pleasure Gardens

The merchant and wealthy classes enjoyed pleasure gardens, which would be laid out in a geometric design. There were wide paths with beds outlined by boxwood as well as a center treatment such as a sundial. The paths were sometimes in a religious cross pattern to reflect the belief that “a garden affords a way to study God’s wisdom and the beauty of creation, Betsy explained. This I didn’t know and will certainly be looking for examples of this when I next visit colonial gardens.

The merchant and wealthy classes enjoyed pleasure gardens, which would be laid out in a geometric design. There were wide paths with beds outlined by boxwood as well as a center treatment such as a sundial. The paths were sometimes in a religious cross pattern to reflect the belief that “a garden affords a way to study God’s wisdom and the beauty of creation, Betsy explained. This I didn’t know and will certainly be looking for examples of this when I next visit colonial gardens.

Gardening was considered an activity for a wise man since he needed to know Latin, math, design, and soil composition. The garden reflected religion, morality, science, and “makes for a hearty, healthy moral home.” I found this interesting because Eudora Welty in her short stories of the South makes references to the idea that the condition of a garden reflects the morality of the owner.

To get the most out of the growing season, glass bell jars and hot frames were used to protect plants from frost. Hot frames look like cold frames but use manure to heat the soil and create warmth for the plants.

Flowers you will generally see in a colonial garden include Love Lies Bleeding, globe amaranth, columbine, as well as roses. Apparently, William Bradford brought rose bushes from England and planted them at the settlement in Plymouth in 1620.

In the better gardens, there would often also be a “folly” (small building of wood or stone used solely for decoration)

In the better gardens, there would often also be a “folly” (small building of wood or stone used solely for decoration)  in the garden, perhaps with a shade well to water the garden. On the edge of the garden would be the “necessary,” or privy, made of brick or wood in a high-style.

in the garden, perhaps with a shade well to water the garden. On the edge of the garden would be the “necessary,” or privy, made of brick or wood in a high-style.

Founders of Our Country as Gardeners

After the American Revolution, the trend was more toward naturalistic gardens to reflect the ideals of the new nation, which included preserving nature and living more simply than those in Europe.

Both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were avid gardeners. Washington freed gardens from geometric design, if only by softening the corners of the beds. He softened the driveways by making them winding instead of straight. He insisted on growing American trees that he gathered from around the country and included red bud (looks similar to a cherry tree), maple, and dogwood trees.

Both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were avid gardeners. Washington freed gardens from geometric design, if only by softening the corners of the beds. He softened the driveways by making them winding instead of straight. He insisted on growing American trees that he gathered from around the country and included red bud (looks similar to a cherry tree), maple, and dogwood trees.

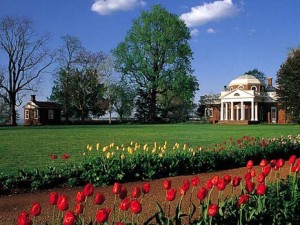

Jefferson strived for practical beauty. He placed Monticello on a hill for the view and terraced on the south side to grow vegetables and fruit for the entire plantation including slaves. He was the first person in the U.S. to grow tomatoes, which were thought to be poisonous by the general population at that time.

The home of John Quincy and Abigail Adams in Quincy, Massachusetts has an historic orchard and an 18th century style formal garden. It contains thousands of annuals and perennials including the Yorkist Rose Tree planted by Abigail in 1788. The scent of lilac trees and roses would waft through the open windows into the house.

The home of John Quincy and Abigail Adams in Quincy, Massachusetts has an historic orchard and an 18th century style formal garden. It contains thousands of annuals and perennials including the Yorkist Rose Tree planted by Abigail in 1788. The scent of lilac trees and roses would waft through the open windows into the house.

This property was more simple and smaller than that of Mount Vernon and Monticello. After the revolution, the open lawn was more curved than linear and with the trees planted at the edges of the lawn the landscape looked more naturalistic.

Restoring a Colonial Garden

So how does one restore a colonial garden that has reverted back to fields, especially if you’re not sure of its exact location? Well, aerial photographs come in handy as they reveal the shadows of the outline and paths of the garden that lie beneath the grassed over fields. Also, the owners frequently left descriptions of their gardens in diaries and journals along with drawings and photographs. The style of the original house and similar ones in the neighborhood can indicate the type of garden grown. Newspapers, catalogs, and surveys of the time can also reveal a great deal.

I’ve been to restored colonial gardens at the Codman House in Lincoln, Massachusetts and the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, Connecticut. You can almost feel the presence of the original gardeners who designed and continually tended to their gardens, showering them with love and devotion. We can see similarities to our own modern gardens especially with plants such as delphiniums, echinacea, and roses, and perhaps pick up some old ideas made new again.

We are lucky on the east coast, especially in New England, to enjoy a plethora of historical properties from our early history that often include gardens. Without fail, the properties and gardens are restored, maintained, and shared with the public by colonial history experts and a group of dedicated volunteers. The Public Gardens section of this website describes several colonial homes and gardens, with more to come!